Calvin

Calvin is named for a sixteenth-century theologian who believed in

predestination. Most people assume that Calvin is based on a son of

mine, or based on detailed memories of my own childhood. In fact, I

don’t have children, and I was a fairly quiet, obedient kid—almost

Calvin’s opposite. One of the reasons that Calvin’s character is fun

to write is that I often don’t agree with him.

Calvin is autobiographical in the sense that he thinks about the same

issues that I do, but in this, Calvin reflects my adulthood more than

my childhood. Many of Calvin’s struggles are metaphors for my own. I

suspect that most of us get old without growing up, and that inside

every adult (sometimes not very far inside) is a bratty kid who wants

everything his own way. I use Calvin as an outlet for my immaturity,

as a way to keep myself curious about the natural world, as a way to

ridicule my own obsessions, and as a way to comment on human nature. I

wouldn’t want Calvin in my house, but on paper, he helps me sort

through my life and understand it.

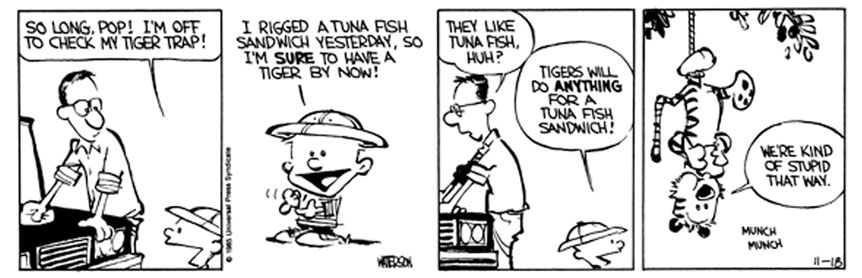

Hobbes

Named after a seventeenth-century

philosopher with a dim view of human nature, Hobbes has the patient

dignity and common sense of most animals I’ve met. Hobbes was very

much inspired by one of our cats, a gray tabby named Sprite. Sprite

not only provided the long body and facial characteristics for

Hobbes, she also was the model for his personality. She was

good-natured, intelligent, friendly, and enthusiastic in a

sneaking-up-and-pouncing sort of way. Sprite suggested the idea of

Hobbes greeting Calvin at the door in midair at high velocity.

With most cartoon animals, the humor comes from their humanlike

behavior. Hobbes stands upright and talks of course, but I try to

preserve his feline side, both in his physical demeanor and his

attitude. His reserve and tact seem very catlike to me, along with

his barely contained pride in not being human. Like Calvin, I often

prefer the company of animals to people, and Hobbes is my idea of an

ideal friend. The so-called “gimmick” of my strip—the two versions

of Hobbes—is sometimes misunderstood. I don’t think of Hobbes as a

doll that miraculously comes to life when Calvin’s around. Neither

do I think of Hobbes as the product of Calvin’s imagination. Calvin

sees Hobbes one way, and everyone else sees Hobbes another way. I

show two versions of reality, and each makes complete sense to the

participant who sees it. I think that’s how life works. None of us

sees the world exactly the same way, and I just draw that literally

in the strip. Hobbes is more about the subjective nature of reality

than about dolls coming to life.